‘The Dawn Club’ began with a deep dive into the archive of the Henry Lawson Centre in Gulgong. The archive exists to record the life and work of iconic Australian writer Henry Lawson and consists of photos, artworks, first edition books, manuscripts which reveal much about Henry Lawson’s concerns – justice for workers, the republic, the plight of the poor, and the emancipation of women. It is the last which is of particular interest for this project – as the ‘Dawn Club’ is about the women in Henry’s life.

After immersion in the archive, I surfaced with sympathy for the women who were closest to Lawson – his mother, lovers, wife, daughter, colleagues and carers. The fragmentary traces of their lives in the archives record the practicalities of women’s lives and their daily personal fight for rights and freedoms that underpins the grand arc of the history of emancipation. Domestic realities often set against the freedom and time to write.

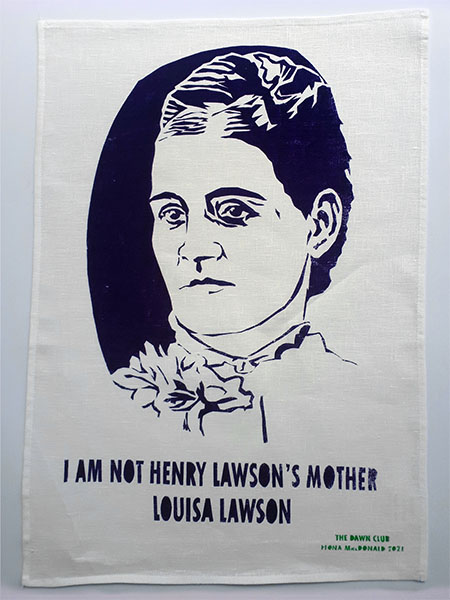

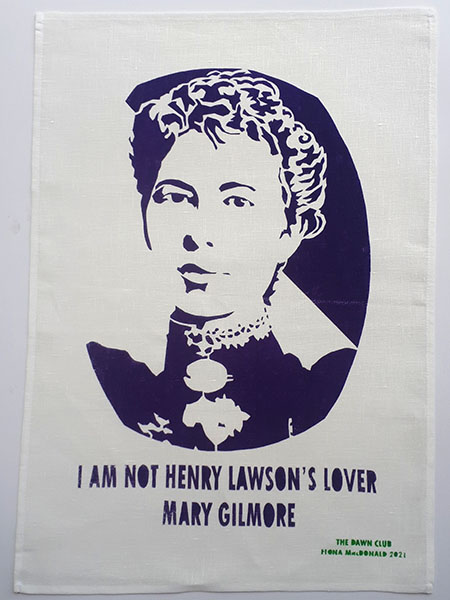

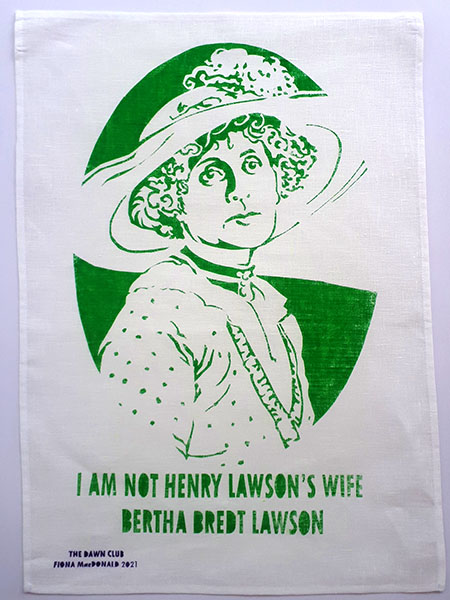

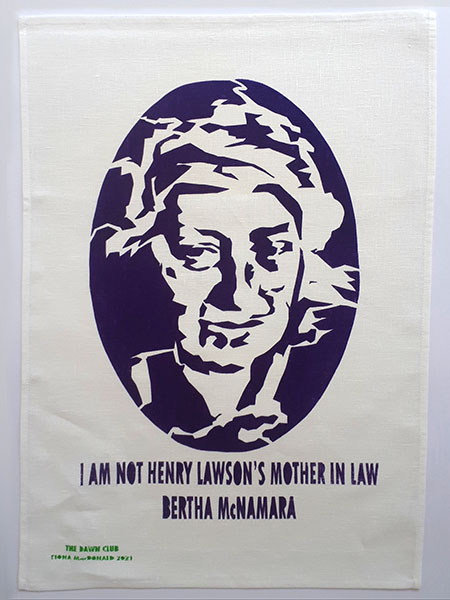

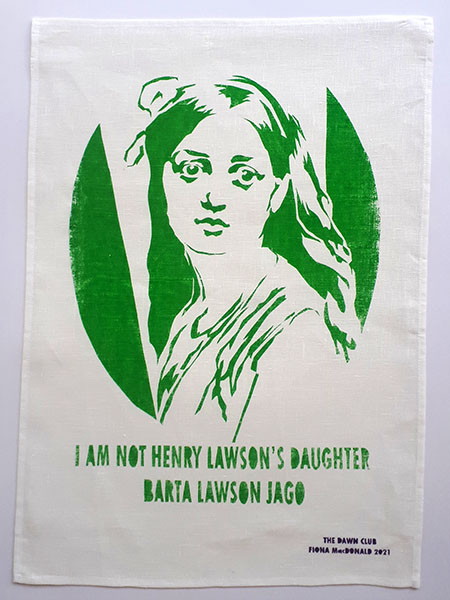

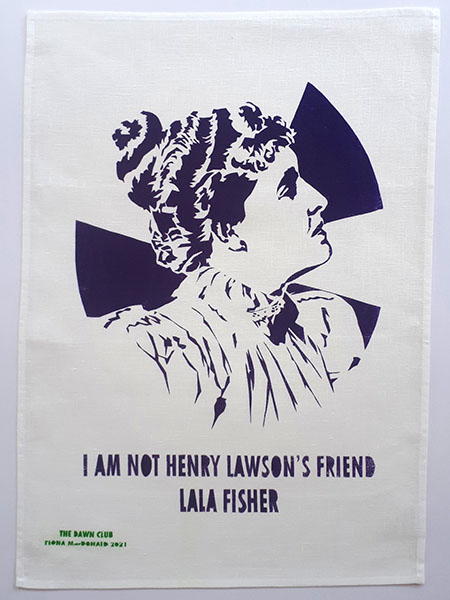

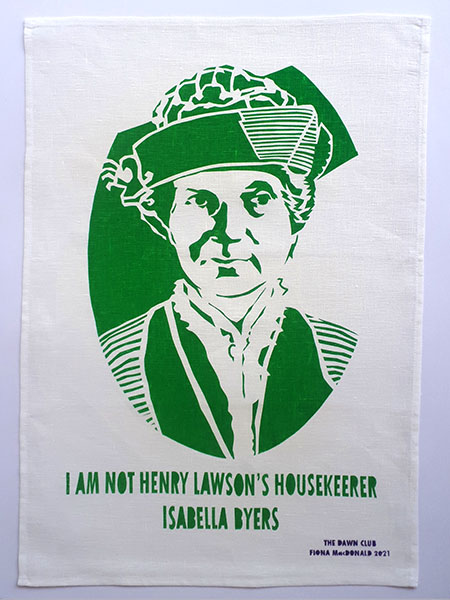

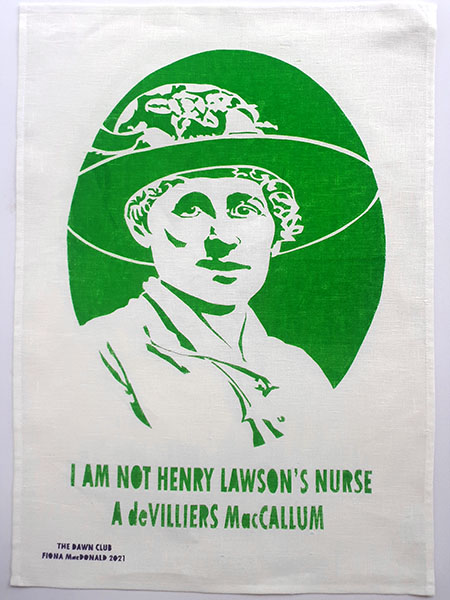

‘The Dawn Club’ is a series of portraits based on archival images of eight of the women who were the closest to Henry Lawson. The portraits cut as paper stencils, screen printed onto fabric and hung from lines strung between the interior walls of the Henry Lawson Centre evokes their domestic realm while each subject in turn denies her connection to Lawson to assert her separate existence.

Fiona MacDonald, November 2021

Dawn Club 2021 is 8 paper stencil screen printed linen tea towels 70 x 50 cm edition of 10. Price: $500 (Postage $15.90 Prepaid parcel post with tracking)

The women pegged on tea-towels around the museum were shadowy yet potent forces in Henry Lawson’s chaotic personal life, from his formative years in Gulgong to his heady Bulletin days and then slow, crumbling decline into alcoholism and early death.

Yet the public record views women as only minor motifs in the gifted poet’s fearlessly ‘democratic’ writingi , where ‘Jack was as good as his master, if not a damn sight better’. Artist in residence Fiona MacDonald pauses the literary spin cycle to consider the absence of women (and we might add First Nations peoples) in the founding literature of Australian democracy and its lingering, nationalist mythology. Lawson was a writer of men, specifically bushmen. The city was a place to be avoided for its wives and its wowsers: those who tamed men and denied their pleasures.

Yet up close, Lawson’s stories and poems are more nuanced than the simple Bulletin stereotype. Lawson’s predilection for authentic representation tapped into an emerging, distinctively modern Australian womanhood. Lawson’s early admiration is embodied in stories like ‘The Drover’s Wife’ (1892) – depicting a tough and reflective woman who seems to be embedded in the very land itself, and whose resourcefulness was in synch with the progressive ferment of the times. Yet Lawson’s admiration was not so steadfast, and when he started to physically and emotionally decline around 1903, he sought the source of his wretchedness in women, whom he accused of “sucking the life blood out of him and destroying his creative gifts”.ii

Fiona MacDonald rinses conventional literary wisdom to restore a female perspective that is usually overlooked. Her tea-towel portraits, screen-printed in the cheerful and determined suffragette colours of green and purple on whiteiii span the museum space like decorative bunting, or crisp lines of laundry hung to dry. They evoke the domestic realm, but each woman depicted exasperatedly tells us that she is not simply one of Lawson’s women, but a person in own her own right.

I am not Henry Lawson’s Mother asserts Louisa Lawson, the educated and aspiring writer and later militant editor of the suffragette journal The Dawn. Instead of cultivating her talents, Louisa found herself yoked to husband Niels Larsen’s incurable gold-fever, and his disastrous prospecting forays left the family nearly destitute. Louisa ‘made do’ running a barely viable farm and shop. She also guided Lawson’s classical literary education and helped to publish his first Short Stories in Prose and Verse (1894), printing it on her own printing press. Yet literary history has damned Louisa’s bad mothering as being the root-cause of Lawson’s instability, alcoholism, and ambivalence towards women. Harsh circumstances harden women and drain mothers of affection, leaving them domineering and unloving – does Louisa sit behind this telling and recurrent theme in Lawson’s work? MacDonald washes this stereotyped maternal stain to seek clarity and avoid the easy blame-game.

Arguably, Mary Gilmore is one woman whose romantic engagement with Henry Lawson did not overshadow her life and achievements. The familiar figure gracing our $10 noteiv reminds us that I am not Henry Lawson’s lover. The renowned writer, teacher, journalist and editor, labour organiser, farmer, family welfare and Indigenous rights advocate was born and raised in small rural townships and bush settlements. Her first volume of poetry was brought out in 1910, and like Lawson, she wrote poetry all her life. In 1893, three years after breaking off her unofficial engagement with Henry Lawson, this intrepid woman travelled with William Lane and others to establish a utopian socialist colony in Patagonia, the ill-fated New Australian Colony, where she started a family.

Bertha McNamara might have been Henry Lawson’s Mother-in-Law, but she is more often acclaimed as ‘the mother of the Australian labour movement’ (a bronze bas relief of Bertha McNamara by eminent sculptor Lyndon Dadswell still hangs in the NSW Trades Hall foyer). This energetic Polish émigré, suffragette, and mother of eleven worked as a travelling saleswoman (jewellery and sewing machines) and later opened a socialist bookshop in Castlereagh Street Sydney. The boarding-house and reading room above the shop became a “famous gathering-point for by socialists, feminists, anarchists, rationalists, Laborites and literary Bohemians”v – including her two famous sons-in-law Henry Lawson and Jack Lang. Bertha wrote and published Home Talk on Socialism in 1891, one of Australia’s first pamphlets on socialism. She continued to write, organized protest meetings in the Domain for imprisoned labour-movement activists in Spain in 1897 and faced hostile crowds when voicing her opposition to the South African War. Not surprisingly, during World War I the shop became an organizing centre for radical, anti-militarist activity.vi

I am not Henry Lawson’s Wife. Bertha Lawson’s voice has been smothered within Lawson’s victim-as-hero story. She comes to us through the poet’s railing against married life, and through brief yet frequent mention made of her mental instability. In 1901, when the couple were sojourning in England, she was indeed briefly hospitalised for some kind of mental breakdown, no doubt partly prompted by the exhaustion of coping in a chilly and unhospitable environment with two small children and an instable husband who liked to drink. After six turbulent years, Bertha divorced Henry for cruelty and for being a ‘habitual drunkard’. Lawson and his acolytes blamed Bertha entirely, but was she really responsible for Lawson’s decline into bitter poverty, alcoholism and early death? If we listen to tea-towel Bertha’s plea; that she was not simply ‘Henry Lawson’s wife’, what do we see? A single parent with two young children, trying to get by within the social mores of the time.vii Bertha asks us to reconsider the discourses of separation, divorce and single motherhood that were emerging alongside suffragette narratives in Australia at the turn of the 20th century.

I am Not Henry Lawson’s Daughter cries Bertha Lawson (Jago), whose image is modelled on a charming 1913 portrait by Florence Rodway, highlighting young Bertha’s beauty and strong-minded presence. She lived scandalously with her future husband, the writer Walter Jago, worked as a librarian, wrote extensively, and was active in the Fellowship of Australian Writers.

Who was Lala Fisher? She was much more than Henry Lawson’s friend. This well-travelled poet hailed from Rockhampton, left town, and never looked back. She was a member of London Writer’s Club, an avowed feminist (and Queensland delegate to the 1899 International Congress of Women) and was a force in Sydney literary, artistic and theatrical circles as a popular lecturer, songwriter and part proprietor of the Theatre Magazine.

Sister Aberta de Villiers MacCallum was clearly not just Henry Lawson’s Nurse, although her name appears in the history of the Darlinghurst Lunatic Asylum as the competent and sympathetic Matron-in-Charge during Lawson’s many later voluntary hospitalisations. It is difficult to uncover more information on her interesting professional and political life. Was she as ardent a feminist and safe sex health pioneer as her New Zealand companion Ettie Rout? Together they established the Home Companions for Australia scheme in response to Britain’s post-war women surplus. They supported patriotic, serious-minded girls who were prepared to rough it and go bush, where white women were scarce. Not surprisingly, only about forty women took up this Imperial challenge.

Mrs Isabel Byers was not just Henry Lawson’s housekeeper, although this generous, older companion certainly looked out for the poet after his separation from Bertha, and when he was at his lowest psychological ebb. Literary history describes her as Henry Lawson’s “Little Mother’ or the “Little Landlady” as he affectionately called her (scribbling a few lines to his friend George Robertson, “I can’t live without her anyhow. I can’t live without a woman messing about me”)viii Lawson also wrote Byers into many of his later poems and stories (eg. ‘Little Landlady’ in Previous Convictions, 1919-21), and was no doubt grateful for her care and acceptance of his alcoholism. It’s hard to look beyond Byers’ ministrations, but her tea-towel portrait prompts us to also consider this diminutive and little-known figure as a smart business woman running successful coffee house and boarding houses in North Sydney; as a literary agent (for Lawson in bad times); and as a fellow poet.

These women were writers, progressive thinkers and hard-working working women who lived unconventional lives. They emerge from Fiona MacDonald’s laundry-tub to tell their own dramatic tales – distinctive stories of modern Australian womanhood that are central to our national character.

Dr Catriona Moore University of Sydney

For further reading download pdf > Download ‘The Dawn Club 2021’ pdf